Gruescript is now in open beta release

Gruescript is an online development system for making point-and-click text adventure/interactive fiction (IF) games. It's designed to create games that feel as close as possible to old-school puzzly parser ("type-in") games, while eliminating the need for the player to type, making it suitable for web and mobile platforms and modern audiences.

Design principles

Puzzlebox games

Interactive fiction (IF) is broadly divided into parser games and choice games. Parser games are the ones where you type instructions into a prompt: >GO NORTH, >GET LAMP, and so on. Probably the most famous parser games are the old ones, like Zork and The Hobbit. Choice games tell you a branching story, interspersed with points where you're asked to make a decision by clicking buttons or links, something like a digital equivalent of the "choose your own adventure" gamebooks, although the games tend to be a bit deeper in terms of what information they're keeping track of.

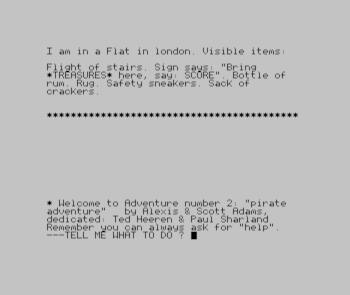

Gruescript has been developed with a certain subset of parser games in mind: the Adventure International titles by Alexis and Scott Adams (not to be confused with Dilbert creator and twitter crank Scott Adams.) At a time when most text adventures could only be played on mainframes at college campuses, the Adamses were the first to target IF for home microcomputers. The need to squeeze a game into the minuscule memories of those machines placed severe constraints on writing. The result was a micro-genre of text adventures with terse, efficient, minimalist prose – room descriptions consisting of a single sentence, plus a procedurally generated list of the objects present – backed up by ingenious puzzle design.

Scott and Alexis Adams' Pirate Adventure (1978)

The technical limitations that made this style necessary were gone within a few years, but the games have remained fondly remembered decades afterwards. Inform creator Graham Nelson wrote that the Adamses' games invoked "the feeling of holding a well-made miniature, a Chinese puzzle box with exactly-cut pieces." I'm going to call this style of game the puzzlebox.

A triangle of dependencies

Inside and outside of IF, development systems, game interfaces, and game design are intricately related. For any given game, or for wider trends of game development, each of these factors influences the possibilities for the other two, and they all feed back into each other. If a certain interface style comes into fashion, more games are designed in a way that fits that style, and more development systems are made that create those games. If a development system becomes popular, more games will be made with it, and those games will tend towards whatever designs and interfaces that system is best at, and so on.

In the last decade or so there's been an explosion in IF forms, and a bunch of new authoring systems like Twine, Ink, and Choicescript. These mostly target mobile and web playability, because it's the 21st century, and create choice games, a natural fit for mobile interfaces. (I want to make one thing absolutely clear: that is awesome. All kinds of IF, from all kinds of author, are valid and welcome and enrich the culture.)

Choice games tend to favour story-centric, rather than puzzle-centric, game design: a high output-to-input ratio, a widely branching narrative, and choices that are pre-defined by the author rather than contextually generated. At every choice point, the player can see all the options available to them, which works best if the player is making a choice for ethical or narrative reasons – which of these options is really the right thing to do? What would my character choose? Which choice will give me the most interesting story? Puzzles, to which there is generally one Right Answer, become a hard problem if the user has to be able to see all of their options all of the time. There are certainly some excellent examples of puzzle-centric choice games, but the authoring systems don't make them easy, at least not for the type of puzzle exemplified by the 'puzzlebox' genre.

On the face of it, puzzlebox game design appears to depend on the parser. The game author has to be able to hide solutions from the player; and the terse prose sits better with a quick-fire, back-and-forth conversation between the player and the game – a lot of the player's commands will be general, mundane actions like moving or picking up objects, and a lot of the parser's responses will be simple acknowledgements. You can't dwell on that stuff.

But if puzzlebox games have to be parser games, you simply can't make them for modern audiences. It's not just that mobile devices don't have keyboards. During the Golden Age of text adventures – in the 1980s when they were produced in their hundreds by companies like Infocom and Magnetic Scrolls, and the hobbyist revival of the early 1990s – entering commands at a prompt was the standard was of interacting with a computer. Today, outside of the tech sector, most users under about 30 simply aren't familiar with the concept. There's still an active subculture around parser games, but they've become unintuitiver and unintuitiver to newcomers.

So, a goal of Gruescript was to identify the qualities of the parser interface that made them suited to puzzlebox design, and create games with an interface that retains those qualities while eliminating the parser itself. With the originality of the true game developer, I'm going to call this kind of interface parserlike.

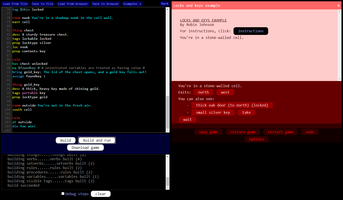

The parserlike interface

Actually, this interface pre-dates Gruescript by about five years. I've made several homebrew JavaScript-based IF games in it, including Detectiveland, which in 2016 became the first non-parser game to win the annual Interactive Fiction Competition (to date, one of only two.) Like many "first non-X" winners of things, it couldn't have won without being as inoffensive as possible to fans of X.

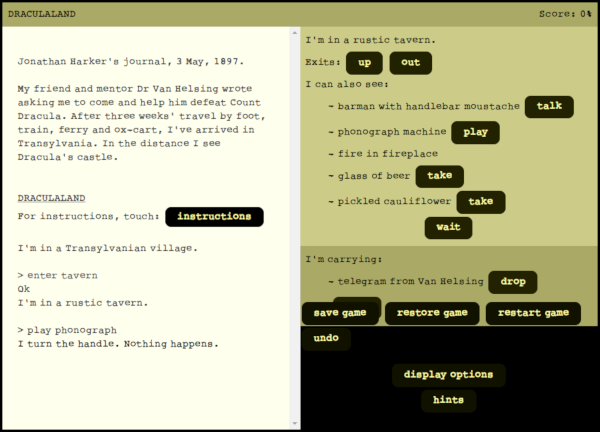

The first game I made with a parser-like interface was Draculaland, again showing my natural flair for imaginative names. There's a puzzle early on in that game – not a particularly hard or complex puzzle, but essentially a parser-type puzzle – in which you come to a graveyard, one of whose inhabitants can be dug up if you happen to have a shovel. The interface implements this by showing the verb button "dig" next to the grave, if and only if you are standing in the graveyard and holding the shovel.

The parserlike interface in Draculaland

What makes this a parser-like puzzle is that you need to make the connection between the shovel and the grave yourself. You then do all the necessary legwork – pick up the shovel, navigate back to the graveyard, and 'hold' the shovel – before you see that "dig" button. Each of these actions is unremarkable, and performed through a generalised interface that doesn't give away any secrets: the fact that you can "take shovel" or "go west" doesn't suggest that the game 'wants' you to do so. No railroad carries you from one end of the puzzle to the other, and you're unlikely to find the path by accident or 'lawnmowering' through finite choices. And your interaction with the game is rapid and responsive enough that it doesn't become tedious. Crucially, you don't know whether your idea will work until you try it. You're thinking like a parser player.

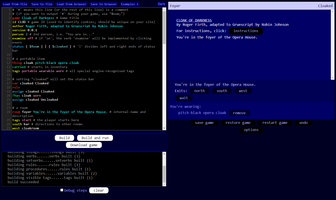

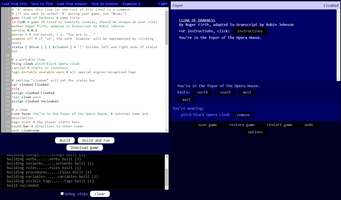

Online development

Gruescript is implemented as an online tool, although you can download it and run it offline if you wish. There's an editor with syntax highlighting on the left (which I made because installing CodeMirror looked like too much hassle – turns out making a syntax highlighter is harder than it looks, pals), and your game itself runs on the right. You develop and bugfix your game here, then download your game as a standalone HTML page, which you can upload to your own itch.io page or elsewhere.

The Gruescript online editor

This is modelled after two tools I admire for their accessibility, cuteness, and strong followings among cool, diverse, weird 'fringe' gamedevs: Bitsy and Puzzlescript. My aspiration for Gruescript is to be interactive fiction's answer to those.

(And if you prefer to develop offline, you can download the whole package; I've even thrown in a syntax highlighting package for Notepad++.)

I called my system "Gruescript" because I'd just done a game about grues and, as I've said, I'm brilliant at naming things.

I'd love to know what you think of it. It's released under the open-source MIT License. Share and Enjoy!

Bugs

I've done my best, but it's a certainty that there are still bugs in Gruescript. Please report them to me at robindouglasjohnson@gmail.com, letting me know what happened, what you were doing, and what browser you're using. Thanks!

Files

Get Gruescript

Gruescript

Create point-and-click text adventures

| Status | In development |

| Category | Tool |

| Author | Robin Johnson |

| Genre | Interactive Fiction, Puzzle |

| Tags | if, parser, parser-choice-hybrid, Point & Click, scripting, storygame, text-adventure, Text based |

| Languages | English |

| Accessibility | Blind friendly |

Leave a comment

Log in with itch.io to leave a comment.